Years ago I took a course in musical cognition in the musicology department of the Hebrew University, and I was frustrated by the huge gap between the cognition that was the subject of the course and the cognition that interested and still interests me.

My interest in the subject was then related to my efforts to learn to improvise in jazz, and the course was concerned with the way the brain processes pitch and the other basic elements of music.

I'm still interested in musical cognition, in how a person thinks in the medium of music. I want to know how a concert pianist commits complex works to his or her memory, how a conductor learns a score and gets an orchestra to play it the way he or she wants it to be played, how a composer conceives of music before he or she writes it out, and how a jazz improviser invents a solo over the harmonies of a standard. The academic study of cognition is very far from explaining matters that complex.

In his popular lectures on music, Gil Shohat often speaks of something quite simple in a classical piano work, such as two descending notes, as a musical idea, which is repeated throughout the piece. While I see his point, and I cannot deny the presence of that feature in the piece, once he points it out to me, the descent from B to A, for example, seems much too simple to be called an idea.

Recently I have been trying to learn the first of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach's duets for two flutes, music that is so full of idea that it's hard to play and follow. I have been trying to give my practice meaning and direction by noticing his ideas and wondering just what I would call an idea if I were analyzing the piece.

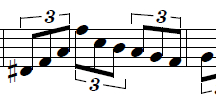

Here's the first measure of the piece:

How many musical ideas do these ten notes convey? One idea is the rhythm, the division of the three beats of the measure into nine triplets. Another idea is the spelling out of the e minor triad on the first beat of the measure, telling the listener (and player) what the key is. A third idea is jumping down from the high 'e' to 'b' and then continuing down the scale rather than extending the initial arpeggio. Yet another idea, and an interesting one, is turning the last note in the measure, the low 'e,' which ought to be, as it were, the resolution of the movement, into a passing note and landing on "d#" at the beginning of the next measure, which echoes the shape of the first measure:

Thus, that shape is also a musical idea.

It would be tedious to go on, as my point is to point out the complexity of both musical ideas and the task of identifying them. Bear in mind, that these two measures appear before the second flute joins in and adds an exponential element to the piece.

Playing W. F. Bach's music is an enriching experience. My purpose in looking for the musical ideas as I learn to play the piece is to play it more intelligently, and also to keep up my interest and avoid playing mechanically as I play the piece over and over again in my effort to master it.

My interest in the subject was then related to my efforts to learn to improvise in jazz, and the course was concerned with the way the brain processes pitch and the other basic elements of music.

I'm still interested in musical cognition, in how a person thinks in the medium of music. I want to know how a concert pianist commits complex works to his or her memory, how a conductor learns a score and gets an orchestra to play it the way he or she wants it to be played, how a composer conceives of music before he or she writes it out, and how a jazz improviser invents a solo over the harmonies of a standard. The academic study of cognition is very far from explaining matters that complex.

In his popular lectures on music, Gil Shohat often speaks of something quite simple in a classical piano work, such as two descending notes, as a musical idea, which is repeated throughout the piece. While I see his point, and I cannot deny the presence of that feature in the piece, once he points it out to me, the descent from B to A, for example, seems much too simple to be called an idea.

Recently I have been trying to learn the first of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach's duets for two flutes, music that is so full of idea that it's hard to play and follow. I have been trying to give my practice meaning and direction by noticing his ideas and wondering just what I would call an idea if I were analyzing the piece.

Here's the first measure of the piece:

How many musical ideas do these ten notes convey? One idea is the rhythm, the division of the three beats of the measure into nine triplets. Another idea is the spelling out of the e minor triad on the first beat of the measure, telling the listener (and player) what the key is. A third idea is jumping down from the high 'e' to 'b' and then continuing down the scale rather than extending the initial arpeggio. Yet another idea, and an interesting one, is turning the last note in the measure, the low 'e,' which ought to be, as it were, the resolution of the movement, into a passing note and landing on "d#" at the beginning of the next measure, which echoes the shape of the first measure:

Thus, that shape is also a musical idea.

It would be tedious to go on, as my point is to point out the complexity of both musical ideas and the task of identifying them. Bear in mind, that these two measures appear before the second flute joins in and adds an exponential element to the piece.

Playing W. F. Bach's music is an enriching experience. My purpose in looking for the musical ideas as I learn to play the piece is to play it more intelligently, and also to keep up my interest and avoid playing mechanically as I play the piece over and over again in my effort to master it.

No comments:

Post a Comment