Sunday, August 24, 2008

Technique and Creativity

Without technique, one's creativity is limited.

True, children are endlessly creative and boldly imaginative, but the limits of what a child can do are evident.

However: the effort to acquire technique often stifles creativity.

The young writer becomes aware of the need to write correctly and stifles her imagination.

The young musician strives to control her instrument and stifles her expressivity.

The young potter concentrates so hard on producing centered, symmetrical, and light pieces that she loses the drive for originality and spontaneity.

For the mature artist, technique and creativity feed into one another. One enhances one's technique in order to create things that were beyond one, and one's enhanced technique spurs one's imagination for further creativity.

When I took up music again after more or less giving up on it while I was in college, I studied for two or three years with Stephen Horenstein, a brilliant composer and virtuoso saxophone player - who became and has remained a good friend. At the time, Steve said that if someone were just playing his instrument without being creative at it, there was no point to it. That was the first time I'd heard that from a music teacher. Up till then the challenge had been to play the notes correctly.

I wasn't ready for Steve's message then and, while I kept on playing saxophone, never really extended myself creatively at it.

About fifteen years down the line I acquired a musical guru of sorts: Arnie Lawrence. Perhaps because I was ready for it, I let Arnie push me hard in the creative direction.

Have I become a creative musician? A creative person?

These are the wrong questions.

I am more creative than I was and more appreciative of creativity when I encounter it.

That's already a lot.

Getting into Pottery

When I was a child of ten or so, my mother enrolled me in a pottery class at Greenwich House, near our home in Greenwich Village, New York City. I was too young to walk to Greenwich House on my own, because I would have had to cross Sixth Avenue by myself, so she took me there. We walked downtown along Washington Square West, where we lived, then to the west on Fourth Street, probably a ten minute walk. It would have taken too much of her time for my mother to leave me, go home, and then come back to get me, so she enrolled in an adult class.

I enjoyed pottery, but after a year or two, all the other boys in the class dropped out, and, I being too young to see the advantage of being alone with a room full of girls, dropped out, too. Meanwhile, my mother remained an avid amateur ceramicist throughout most of the following years.

The idea of taking up the craft as an adult never occurred to me until a few months ago.

I looked up pottery classes on the Internet and spotted one that seemed appropriate from every point of view - it was within walking distance from my house in Jerusalem, the price was not too high, and the hours were extremely flexible. I called up the teacher right away, arranged to go to see her setup, and within a day or two I was sitting at one of her wheels, struggling to center a rapidly turning lump of clay.

Hadas, my teacher is a tall, thin young woman, and her studio is in two front rooms of a small rented apartment in an extremely expensive neighborhood. She has four wheels, a kiln in a shed outside her door, and the clay, firing, and glazes are included in the price of the class. The downside of the flexibility she offers us in scheduling our sessions is that she constantly has to juggle us from one slot to another. Because my time is pretty much in my own control, I have attended classes on various days, at various hours, and so met many of her students. They are mainly women, but now I don't mind that.

Hadas' teaching method is low key and unintrusive. She lets us work on our own and waits for us to ask her how to do things. That suits me perfectly.

I think I would have been happy as a potter. If I'd stuck at it as an adolescent, I'm sure I would have gotten more and more deeply involved in it, maybe gone on into it. But who knows? There were so many external pressures on me at the time, pressure to excel academically, pressure to get into a fine university and qualify for some prestigious kind of work, that I wasn't ever in touch with what I wanted. I can't imagine that I would have considered going to art school and majoring in ceramics in the face of all that pressure, for I had completely internalized the values it came from. I thought that art school was for people who weren't good at other, more important things.

Now, however, as I approach my mid-sixties, having done all the things I was supposed to do, more or less -- received a BA from a prestigious university, earned a doctorate at another prestigious university, worked for decades as a translator (in other words, I put my intellectual gifts to some kind of use), raised a family, and so on -- I feel as if pottery is the artistic medium I have been searching for all my life.

I always wanted to be some kind of artist, but never got it together to become one. Since I'm very verbal, I thought I ought to be a writer, that if I had an artistic medium, it would be words. Indeed, I have had some modest success as a writer and translator, but I never felt delight in what I wrote. I also have some visual skills, and I was seriously involved in photography for a few years, but there, too, I didn't find that I was taking pictures that anyone else couldn't have taken. When I was doing photography, it was more a way of running away from my disaffection with graduate work than involvement in the thing itself.

I am also a serious amateur musician. I play saxophone and clarinet and even went back to university to study musicology half time for three years. I love hearing and playing music, but I'll never be seriously good at it. Not that I mind. I'm not ambitious as a musician. I'm glad to have opportunities to play, and I enjoy it. It's refreshing to do something without being ambitious about it. Perhaps ambition is what took the pleasure out of writing for me - but let's not go into that for the moment.

Sunday, August 3, 2008

Smashing all my Pots

When I asked Hadas, my teacher, whether that would be possible, she told me that I had made an irreparable error: I mixed different kinds of clay that have to be fired at different temperatures. So she can't fire them for me.

It is true that if I had my own kiln and my own glazes, I could have glazed and fired them all at a low temperature, but I'm far from there. So the only thing I could do was smash them all and soak them in water to reclaim the clay - which remains clay that I won't be able to glaze, though I can fire it.

Early this morning I went down to the studio and broke up almost all the vessels I had thrown over the past three months. I put them in a tub of water to turn them back into raw clay, which I've decided to use for projects that don't need glazing. Maybe I'll make a bunch of flower pots, for example, and some sculptures. This morning I started in that direction. But I'm prepared to smash all that in a month or two.

Oddly enough, I have absolutely no regrets about any of the pots that I destroyed. My standards have been going up as my skill has increased, and I didn't see much point in firing and glazing a bunch of heavy, lopsided, clumsy pieces.

Many teachers of pottery impose stringent discipline on beginners, making them smash every pot that isn't centered. Hadas, the teacher I've been going to, is more laissez faire, and she's right. Sometimes clumsy pots have a charm of their own. Why discourage people when they're doing pottery for the fun of it?

Tuesday, July 22, 2008

Intelligent Design

It is argued, for example, that something as complicated as the vertebrate eye could never have evolved by chance, without a guiding intelligence.

But why design eyes that weaken as we age, that are subject to blindness and disease, and that are limited the way ours are?

For that matter, why would an intelligent designer give us teeth that rot and gums that recede?

There's so much palpably wrong with the little piece of the universe where we live, that one might go so far as positing an absent-minded designer with occasional flashes of intelligence and a nasty tendency to play practical jokes.

Wishes and Fulfillment

At my age, some of the things desired by people in their thirties, who are launching themselves into life, don't seem relevant. I'm more modest in my ambitions: maintaining decent health, living to see my grandchildren reach maturity, making good use of the time allotted to me.

A friend of mine fantasizes about travel, about renting a barge and floating down the canals of Europe, about buying a camper and roaming about the North American continent, and in fact he did something a lot of people imagine doing but never get together: he and a couple of friends, men in their late sixties, bought huge motorcycles in California and zigzagged across the US and Canada for a few months.

My fantasies are more about staying put than about traveling.

One recent fantasy that I'm living with is to install a pottery studio in our home and devote much more time to ceramics - my latest passion - than I am doing at present. I'm halfway there, in fact, because an acquaintance of mine, an accomplished ceramicist, is allowing me to use her studio two days a week.

Another fantasy is to create a music studio, with sound equipment, and to play and write music. I imagine writing arrangements for the big band I play in.

Another fantasy is to get a regular gig in a pub with my pianist friend and play standards. I'm too shy to move forward on this, but it's certainly possible.

And I entertain fantasies about importing musical instruments and opening a woodwind store. This is not a serious idea!

Interestingly, I don't have fantasies about writing a hugely successful novel or anything else connected with writing and literature, though that has been my main occupation all my life.

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

Four Kinds of Playing: Number One

Recently we hosted a concert in our home. A friend of ours is a classical singer. She had prepared a recital of Lieder with an excellent accompanist and asked if we would be volunteer our living room and grand piano. We agreed. Indeed, we have had quite a few chamber music concerts in our living room, and our piano has been played by some superb musicians. (I always feel that when a master plays an instrument, the instrument absorbs some of the mastery.) I thought, though, that it would be only fair to ask a small favor in return, so I prevailed upon the pianist to accompany me in a short piece, “Danse,” by Darius Milhaud for alto saxophone and piano. You can hear a fine performance (not by me) of that sweet piece on this website: http://www.dcmusicaviva.org/recordings/documents/dance.mp3

Playing a piece like that demands, first of all, precision. You have to play all the notes exactly the way the composer wrote them, in time, in tune, articulated the way it's indicated on the printed page, with the correct dynamics. The challenge for the musician is to play as accurately as possible and, at the same time, to play the piece expressively, not mechanically.

Last year Judith and I attended a Scarlatti and Bach marathon, which was part or the Israel Festival. Six young pianists took turns playing, and we were enthralled not only by the excellence of their performances but also by the palpable differences in their approach – even though they were all playing the notes “as written.” It was a great lesson in interpretation.

My performance went okay. I was nervous and came in wrong a couple of times, but the accompanist never blinked and stuck right with me, and I don't think anyone in the audience noticed. If I had had more time to rehearse with him and develop a musical rapport, it wouldn't have happened. I enjoyed myself, but only so much. My conclusion was: I don't want to spend time and energy in preparing a recital of classical saxophone pieces (and imposing it on my friends), My self-image as a musician has changed.

Private Adventures

Some of my more polite friends occasionally ask me what I'm working on, and sometimes, when I'm enthusiastic about a job, I'll tell them more than they really want to know. However, I'm deeply aware that my work entails intense, private experiences, which, paradoxically, because it's all about communication, is almost impossible to communicate. There's nothing outwardly dramatic about it. I'm not driving a car very fast, thrashing through a jungle, arresting violent criminals, or engineering billion dollar buyouts. There's also very little at stake – even if I get a sentence in a novel completely wrong, no one's going to suffer very much from my error. But I care deeply about getting the right word or expression, about making a sentence read well, about conveying the author's voice and ideas.

In the end, the locus of human experience is in the heart, not out in the world, and the essence of civilization is caring infinitely about things that don't have many practical consequences.

Summer Jazz School

In the winter of 2004-5, I did a web search for “jazz summer school” and up came the Dordogne Jazz School, run by English musicians in a dilapidated medieval castle in a hamlet called Monteton in the rural countryside near Bergerac. It sounded very attractive, and I had some correspondence with the director, but I didn't manage to get well enough organized to sign up that winter. The following year I resolved to do it, and by December I had reserved a place. I made plane reservations in the early spring and even thought ahead to reserve a hotel room in Bordeaux for the days before and after the jazz school. As I geared up mentally and musically for a week of jazz, the war started here in Israel – making me rather less enthusiastic for the pleasures of life, including making music.

I was a bit apprehensive and imagined the school would be populated by ambitious, young, talented musicians, who would be too stuck up to play with me, or, alternatively, with rank beginners from whom I could not learn very much. However, I assumed that I would be playing a lot, and that would be valuable.

The trip there was not fun. My flight left Ben-Gurion airport after midnight on Sunday, July 30 and, I arrived in Charles De Gaulle airport with an hour or so to get to the Air France window and get a boarding pass for the connecting flight to Bordeaux. The line was so long and slow moving that I almost missed the plane. To top things off, when I got to Bordeaux, I found that Air France had abandoned my suitcase in Paris.

My hotel in Bordeaux was very easy go get to from the airport, and the people at the reception desk were pleasant. I had arrived before check-in time, but my room was ready, and they had no objection to my going in and resting for a while. Although I was exhausted, after resting for a while, I went out and spent a very pleasant day in Bordeaux, which is an impressive city, full of grand eighteenth century buildings, next to a very wide river, but with a historic center small enough to walk around easily. Since it was Sunday in the holiday season, there were very few people in the streets.

As promised, my suitcase was brought to the hotel in the late afternoon. The people at the hotel said it happened all the time. On Monday morning I packed and then took the long walk from my hotel to the railroad station, because I love wandering around towns, and bought a ticket for the 13:35 train to Bergerac. I slowly made my way back to the hotel and checked out at about eleven. There is a tramway that goes directly from where my hotel was, a big park with the strange name of Quinconces, to the railroad station. I have since discovered that “quinconce” refers to an arrangement like the five on a die or a domino: a square with four dots in the corners and one in the center, which is the way the trees are planted in that park. I had a cup of coffee, got on the tram, and had time to eat a salade niçoise in a decent restaurant across form the station (and to have my first of many glasses of red wine) before my train left.

The train to Bergerac goes through wine country, past places like St. Emilion known for their vintages. Upon arrival in Bergerac, I followed instructions and crossed the street to a café to wait to be picked up by Simon, the summer school's driver and trouble-shooter, an English expat who seems to enjoy life. At the café a tall, balding young man saw that I was carrying a sax case and figured out that I was also headed for the school. His name was Christophe, he's a pianist, and he works half-time in computers and half-time as a volunteer political activist for a small socialist party in Paris. It turned out he was our token Frenchman in the course, though we had a French-speaking Swiss engineer as well.

Christophe and I had a beer together, and he called Simon on his cell phone once he figured out the number from the way it was printed out on the email I had received – my Hebrew oriented computer had reversed the order of the numbers. The drive to Monteton was unexpectedly long, partially because we stopped at the the small local airport to pick up Mike, another pianist, but Simon was entertaining, as was Christophe.

I was still uncertain how things would turn out musically. We pulled into the castle and took out our luggage, but our rooms weren't ready yet, and we didn't know whom we'd be rooming with. In fact, no one in charge seemed to be around to deal with us. We hung around and chatted, about twenty of us, in a pleasant area between a dilapidated stone tower, a terrace with tables set up for dinner, and a low, nondescript building. After a while, some people gathered at the bandstand and started jamming. There was a British bass player named Rick, with a thatch of graying blond hair, and a drummer. Christophe sat down at the keyboard, and I took out my alto. What the hell, I said to myself, why be bashful? After all, I had paid the airfare and tuition to play. I can't remember what tunes we played, but we hit it off fairly well. Other people took out their horns, and we kept going for quite a while. When you think about it, which I have done a lot, it's rather amazing that people who have never met can start making music almost immediately.

Dorian Lockett, a bass player who, with his wife, Andrea Vicari, a pianist, run the school, eventually showed up, and we were gradually settled in our rooms. Andrea's parents have a house nearby, and their two children stayed with their grandparents. Her brother Scott, a drummer, was also around helping out and playing. Dorian more or less takes care of the administrative stuff, and Andrea is in charge of the musical program. I was placed with two other guys in a long, narrow, extremely basic room, with an adjoining bathroom that was even more basic. I'm not complaining. The beds were clean and comfortable, there was hot water for showers, and my roommates were considerate.

I had registered as a vegetarian to avoid problems with kashrut, and at dinner that was no problem – nor was it ever. The restaurant staff was extremely thoughtful and friendly. The food was generally fine, never very ambitious, but always satisfying, with plenty of salad, as much wine as you could drink at lunch and supper, and fresh bread home baked from organic whole wheat flour. They served great cheese after every meal, of course. There was also a bar where you could buy coffee, soft-drinks, beer, wine, or whiskey.

Look how far I've gotten, and I've barely begun to describe the musical activities. Dorian sent us a .pdf file before the school began, with the schedule, which I printed out and looked at, but it didn't really mean much to me. On Tuesday morning we started off in earnest, and I began to see how much care had been put into planning things. We were placed in two different groups, which met at different times, of course. One was known as a workshop group – each one had about a quarter of the forty participants, selected by instrument. My group, in memory of the confusion of the first evening, was known as the Bed-Hunters. (Another group was known as the Jazz Worriers – to give you an idea of the humor of the place.) Each workshop group met for two hours or so every morning and prepared a piece for performance that evening. We also had three slightly larger ensembles, a Mingus group, a Soul group, and a Salsa group (which I chose, because I'm pretty weak on Latin rhythms). Those groups prepared performances for the final evening of the school, except for the Salsa group. We played three pieces for dancing at a Salsa evening on Friday. We also had instrumental sessions with the teachers, master-classes, and improvisation lessons.

We had classes from ten to one and then from four to six, and organized jam sessions and performances till eight, when we had supper. After supper sometimes our teachers played for us, once a French group that was sharing the facilities with us gave a concert, and so on. There were disorganized jam sessions until the wee hours of the morning. I stayed up till one-thirty or so one night, but I didn't get much out of that part of the program.

We had four main teachers: two saxophone players, Julian Siegel and Ingrid Laubrock; one trumpeter, Chris Batchelor; and one guitarist, Phil Robson. Andrea worked with the pianists. They are all fine musicians and excellent teachers. Chris was especially articulate, and, since he directed the Salsa band, I was exposed to him a lot.

Julian was the first teacher I was exposed to, in a workshop for the advanced saxophone players (it was up to us to decide what level was right for us). He's a tall man with a soft face and a lot of black hair. He speaks quietly, almost bashfully, and in his class he emphasized sound production in the lower register of the horn: the most basic stuff is also the most advanced. That afternoon he also led my workshop group and taught us the song “Sweet Georgia Bright” by ear, going over it patiently, phrase by phrase, chord by chord, till we'd got it. Like all the other teachers, he was terrifically encouraging, telling us we were doing great all the time.

My biggest obstacle to improvising with assurance is my tendency to get lost in the form (or my fear that I'll get lost). I tend to compensate by gluing myself to the lead-sheet, using my eyes instead of my ears, so it was very useful to me to learn something strictly by ear, without the safety net of written music.

Chris Batchelor, a strong and imaginative trumpet player and a very articulate teacher, addressed a lot of the musical issues that concern me at the moment in a way that I could grasp immediately. He led our workshop group the next day and taught us a simple, amusing New Orleans inspired Bill Frisell piece called “In Deep,” also by ear. He also gave a master class demonstration that day, about breaking out of the patterns of jazz standards by changing phrasing, by playing the chord progressions out of phase, and other fairly technical matters. That mainly drove home for me how firmly you have to have a piece in your mind, in order to improvise against the structure and not confuse yourself.

But I don't want to go on about the specific things I learned, things that I want to work on and use now that I'm back home. The main point is that by the end of the week, a lot of us were sounding pretty good, playing confidently with a full tone, and enjoying ourselves. People who had never met had formed ensembles and were playing together nicely. Andrea and her brother Scott supervised the early evening jam sessions and made certain that no one got up on stage and monopolized the action, and the atmosphere among us was uniformly generous. People always applauded your solos, even if you got lost and sounded like shit.

What may be surprising is that there are enough people like me, mainly middle-aged amateurs, who are serious about our music to populate a school like this. The other thing, of course, is that this was a demonstration that jazz has convincingly become a world music – you don't have to be American or African-American to love it or play it creditably. At our final concert, on Sunday night, August 6, our performance groups played: the Mingus band, the Salsa band, and the Soul band. The Mingus band started off with “Better Get Hit in the Soul,” a lively evocation of black evangelical churches. There they were, about twelve white Europeans playing the blackest of black music with enthusiastic respect. And then another twelve northern Europeans played Cuban music with love and abandon.

I've always looked at my musical activity, at least in one sense, as something that takes me places – and indeed it has.

Review of an Agnon Novel

Here's a review that appeared on a good web site:

National Yiddish Book Center - A Simple Story by S.Y. Agnon

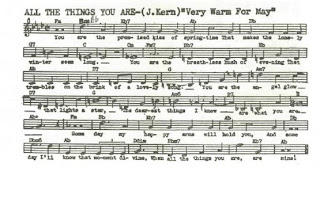

All the Things You Are - an Appreciative Analysis

in Praise of a Song

This song has been played so many times that people take the elegance of its construction for granted. When you learn to play the melody, you appreciate the logic of it, the way it descends from the first A flat down to a B natural in the fifteenth measure, leaps up to a D natural, again descends to a G sharp, which metamorphoses into an A flat and begins a descent again, a descent which is interrupted with some upward leaps, until it finally settles on an A flat, the basic tonality of the song, at the end. It's deceptively simple, deceptive because the descents move through some surprising notes that don't belong to the key in which the song is written.

Harmonically, it is very sophisticated. It starts off by establishing the key of A flat major in the first four measures, with an absolutely ordinary sequence of chords, VI7-II7-V7-I, which one typically finds at the end of a classical piece. In the next four measures, it takes us to a surprising place harmonically with a daring transposition that sheds four flats in three measures, by moving from D flat major (a chord appearing in the key of A flat with no accidentals) to G7 (a chord that sheds two of the flats of A flat, the B flat and the D flat), which resolves to C major.

Then it jumps back to a key much closer to the original key of A flat major, when the C major chord turns into a C minor chord, and we have a repetition of the initial chord series (VI7-II7-V7-I) but in the key of E flat, the dominant of A flat – so after the digression to the unrelated key of C major, we have returned to a harmonic movement typical of classical movement: modulation to the dominant. However, instead of staying in that key, in a sequence of chords identical to that of measures five to eight, but transposed up a fifth, we modulate to the entirely unrelated key of G major, exactly one half tone below the initial key of A flat major, which means that in the space of sixteen measures, the song has moved almost as far as possible from the originally key. (If you lay out the twelve possible keys in the diatonic scale in the order of the cycle of fifths, you get:

Ab – Db – Gb (F#) - B – E – A – D – G – C – F – Bb – Eb- Ab

So the keys of either A or D would actually be farther away from A flat than the key of G, but it's still a very bold modulation.)

The third eight measures of the piece, the bridge, begins by establishing the key of G major with chord progression typical of classical harmony: II – V7 – I. Then, however, the second half of the bridge jumps to an unexpected key: E major. The chord progression that Jerome Kern (assuming that the chords that appear above are the ones he wrote) put in is A minor, B seven, E major. The A minor seems to be repeating the chord progression of the first four measures of the bridge, but instead of being II in the key of G major, it becomes IV in the key of E major, since the following chord is a B seven. In fake books that reflect the way jazz musicians have reharmonized the song, an F sharp half diminished chord is substituted for the A minor (the chords have almost the same notes, F#, A, C, E and A, C, E, G respectively), so you have what jazz musicians call a two-five to E – except ordinarily the half diminished chord ordinarily indicates a minor key, and this progression leads to a E major. The last chord of the bridge, on the twenty-fourth measure, is A flat augmented (Ab, C, E) – a chord that can be also be thought of as C augmented and E augmented, because it's made of three equal intervals, major thirds. Harmonically, augmented chords don't fit into any ordinary diatonic scale (except the melodic and harmonic minor scales, which are not, strictly speaking, ordinary), and composers use them to shift keys almost any way they want to. Here, if you think of the chord as a C augmented chord, it can be used to move the harmony back to F minor, which is where the piece began.

The last part of the song repeats some of the material from the first part but expands on it, and, unlike the first part, it finally lands squarely in its home tonality: A flat major. The chords in the first five measures of this section are the same as those of the first five measures of the piece, but instead of jumping to an unexpected G7 chord after the Db7, the way Kern wrote it, it stays in the tonal territory of Db, the sub-dominant of Ab major and ends with a classical cadence: Bb min7 - Eb7 – Ab. Those measures are reharmonized in various ways in different fake books that I have seen, to make the final cadence stronger.

Another way of thinking about the harmonies here would be to say that the song can't decide, at first, whether it's in Ab or C. The first eight bars end on C, the second eight bars end on the dominant of C, G, and the bridge starts off in G. The bridge ends in the key of E major, which is exactly halfway between C and Ab, and the final chord of the bridge is that augmented chord which fits both into the key of C (C,E) and of Ab (Ab,C). In the last twelve bars (in the printed version I appended at the beginning, the final bar of the piece is missing), the song makes up its mind. If the last part of the song were a simple reprise of the first eight bars, which is very common in the type of song known as “standards,” to which “All the Things You Are” definitely belongs, it would in fact end in the key of C. However, the second to last four bars, which correspond to bars five through eight, and on a d diminished chord, as Kern as harmonized it. (In some fake books this appears as a B diminished chord, which is made up of exactly the same notes, with a different bass.) From there Kern puts us squarely in the key of Ab major, although the second to last melody notes, F, G, could actually be heard as the seventh and root of G7, resolving into C major rather than Ab!

Monday, June 9, 2008

Konch Magazine

But it's archived in an obscure way there, so I'm copying it in here.

From the Schizophrenia of American Racism (the Frying Pan) to the Paranoia of the Middle East (the Fire)

by Jeffrey M. Green

On the photographic paper under the enlarger my white face was black and their black faces were white. If we exposed the print so that the features of their faces were clear and distinct, my face would be so underexposed that I would look like a featureless ghost, and if we exposed it properly for my face, theirs would come out like bottomless shadows. So I explained the technique of dodging to them. After we exposed the print long enough for their faces, I waved my fingers over them to shield them from the light while I continued the exposure long enough to expose my face properly. My students thought this was a riot. Not only had photography reversed black and white for them, but it had made my white face into a problem that had to be solved. They joked with me about it, and for that moment I had gained their trust, in the darkroom, where we were all invisible.

This incident took place in the summer of 1968. I was a twenty-three year old graduate student in Comparative Literature at Harvard, and I had come to Charleston, South Carolina to teach in an Upward Bound program. I had no illusions about the enormous gap of privilege that separated me from my students, but in the safe and nurturing atmosphere of that program, which was run by some self-assured and impressive southern black educators, I was accepted by my students, who probably had never had a white teacher before. We learned a lot from each other. During that summer it often happened that I would be the only white person in a crowd of African-Americans, and I sometimes forgot how conspicuous I was. Once we took our students to the University of South Carolina at Columbia for a meeting of all the Upward Bound programs, and while I was standing with my students, I happened to catch the suspicious gazes of students from another group. Suddenly I sensed the hostility toward white people that black high school students in the south felt but rarely could express openly. You might recall, though, that there was extensive rioting in Charleston a year afterward. Hostility can't be bottled up forever.

Here's the schizophrenia. During the week I lived in a boarding house in a black neighborhood of Charleston. My landlords, the Brevards, were an elderly, proper couple. Mr. Brevard was a retired railroad chef, and occasionally he would cook gourmet meals for me and my roommate, a student from Bombay who was studying at Carnegie Tech. But I spent the weekends with my fellow Jews. A relative of mine had married a doctor from Beaufort, South Carolina, and I visited them several times. Also, before going down to Charleston, I had received the names of several members of the local Jewish community, who were extremely hospitable to me and approved of what I was doing. So I sometimes found myself switching from the Brevards, clean and comfortable but somewhat rundown home to air-conditioned ranch houses in Charleston's affluent suburbs. One of the Jewish families that I came to know in Charleston had a forty-foot racing sloop, and they often took me out for sails. So there I was, with one foot in the poverty program and another foot on a yacht. I went to the African Methodist Episcopal church with the Brevards to see what that was like, and I went to the elegant Reform synagogue in Charleston with my Zoroastrian roommate.

My schizophrenic experience in Charleston was, in essence, no different from what I had known for most of my life. I grew up in Greenwich Village in the 1950s and went to a progressive private school, the Little Red School House, where we were taught not to be prejudiced. In elementary school we studied about Mexico, India, and China, and also what was then called Negro History. How many other fifth graders in the US at that time were taught about Toussaint L'Ouverture and the Haitian rebellion against France? We sang spirituals in music class, and, in fact, our music teacher was a charismatic black woman, Charity Bailey. Looking back on it now, I realize that it was very unusual for a class consisting mainly of middle-class white pupils to have a black school- teacher, but at the time I thought it was entirely natural. Charity (we called our teachers by their first names) was an amazingly gifted teacher and handled her blackness with admirable poise.

I went on from the Little Red School House to its upper school, the Elisabeth Irwin high school (where Angela Davis was a year ahead of me). The political commitment to integration and civil rights was even stronger there. We sang "Lift Every Voice and Sing"along with the "Star Spangled Banner," and we regularly spent Saturday mornings picketing the Woolworths on Fifth Avenue near Fortieth Street, because the lunch counters in southern Woolworths were segregated. But at the same time, Elisabeth Irwin found it hard to recruit African-American students. The tuition was kept as low as possible, and scholarships were made available, but not that many black people could afford to send their children to private schools, and those that could were not interested in a leftist, progressive school like ours. So the integration in my school was more token integration than the real thing, despite our ideals.

Outside of school, my life was just as segregated as any other middle class white American,s. My parents had no African-American friends. I never played with black children or went out with black girls. And I was under tremendous pressure to get into a "good college. Only one of my classmates had the courage of his political convictions and attended City College, where there was some likelihood of studying with a significant number of people of color. Looking back on it, I see how abnormal it was to be in favor of civil rights, against segregation, and so on, and also to protect my white middle class privilege with vigorous tenacity.

In 1969, while I was partway through my graduate program, I had the opportunity of teaching English in a southern Negro college. I was offered a job at Tuskegee and also at a college in Houston, Texas, but I chickened out. I opted to remain in the safe environment of Harvard and

finish my doctorate (which has proven to be a virtually worthless credential, since I did not become an academic). I can,t complain. If I,d gone off to teach at Tuskegee, I would never have met the woman I married, and our marriage has been very rewarding. But my life would certainly have had a very different shape.

For one, I probably would not have moved to Israel in 1973.

To some degree, the decision to move here was an effort to escape American racism, to escape the burden of being white in a society that oppresses people who aren,t white. I heeded the cry of Huey Newton (I think it was he who said it): "If you,re not part of the solution, then you,re part of the problem. I was unable or unwilling to make my whole life over to become part of the solution, so I decided to evade the problem by moving away from it. How naive I was! Instead of being privileged by my skin color, in Israel I am privileged both by being Jewish (with respect to Palestinian Arabs) and by being of Ashkenazic (European) origin (with respect to Jews from North Africa and the Middle East). Also, as if to compound the irony, during the past ten years or so I have become increasingly interested in jazz, and that interest has led me to read extensively about issues of race and African-American culture. So not only have I not escaped American race issues, I have found myself in a violent stew of ethnic conflict in which I am no less compromised by the unearned, accidental privilege of my Ashkenazic Jewish birth than I was as a white-skinned citizen of the United States.

For someone who grew up in the racial society of America, it is difficult not to see the social problems of Israel in the same light. That is my point of reference, but it is not necessarily a useful one. The crimes committed against Africans during the slave trade and under colonialism, and to African Americans under slavery and since then, are not at all the same as the suffering undergone by the Palestinians as a result of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Which is not to deny that very deep scars have been left on Palestinian souls. Conversely, being here in the Middle East has changed my view of the issue of race in the United States. Despite my white skin and European features, I don,t look all that different from many Arabs and Oriental Jews. Although they tend to be darker than I am, some of them are just as light, even blond. The main difference between me and them is cultural. Seeing this, now, has shown me what I had been blind to as a liberal, white American in the fifties and sixties. I tended to discount the cultural difference between me and African-Americans. I failed to realize that African-American culture was really a culture, and I didn,t understand why there had to be Black Studies departments at universities. I wanted desperately to regard American Negroes as white people who happened to have dark skins. That,s how I viewed civil rights. Since "they are the same as "we are, "they deserve the same rights. I hadn,t fully grasped the notion that "they deserved full civil rights even if "they weren,t the same as "we were. Moreover, now that I think of it, it was odd that I, as a Jew, thought of myself as part of the white American collective, while at the same time I insisted that Jews should both enjoy full American citizenship and also preserve certain distinctive religious and cultural traits. We Jews are often accused of being clannish, and I felt

we had every right to be that way if we wanted to.

As an American who grew up committed to civil rights, I am sensitive to the prejudice and discrimination practiced in Israel against Oriental Jews and Palestinians, and as a person who has lived in the cultural stew of the Middle East for nearly thirty years, I have become sensitive to the cultural aspects of discrimination against African-Americans in the United States. As an American troubled by the unearned privilege of having white skin, I suffered from a kind of schizophrenia. As an Israeli, surrounded by real enemies, many of whom have every intention of killing me and my family, I run the risk of suffering from paranoia. I can,t assume that Palestinians will stop hating Israeli Jews if we start treating them fairly. I still have to deal with the cognitive dissonance of being a privileged person who doesn,t believe in that kind of privilege, but I also have to protect myself. And it,s never clear how real the threat can be. I have joined groups of Israeli peace activists on visits to Palestinian villages in the West Bank, and I have felt safe and welcome. But I also was within sight of one of the suicide bus bombings that took place in Jerusalem in 1996. If my car had been stopped a couple of hundred feet closer to the traffic light, I could have been injured. If I had sent my son to the Central Bus Station by bus that morning instead of driving him, he might have been killed in that explosion.

I have used the words "schizophrenia and "paranoia loosely here. I,m not a clinical psychologist, and I don,t really claim that these situations have made me mentally ill. But sometimes I feel as if what stands between me and the mental illnesses that go by those names is insensitivity. Not only is my skin white, it is thick. If all of us were fully sensitive to the contradictions between the values we profess and the values we actually live by, we might all go mad. Or else we might change the world.

Sunday, June 8, 2008

Doing Listening - Sonny Rollins, "The Stopper"

It ought to. After all, I am a dedicated amateur saxophone player and I usually practice for at least an hour a day, except on the two or three days a week when I play with groups. Playing music on an instrument seems to be “doing something.” For three years I took university courses in musicology. Listening to music for my courses was “doing something.” For that matter, attending a concert also enjoys the status of “doing something.” I would never think of bringing a book to a concert and reading it, even if there were enough light to do that. So why is it that when I hear a live orchestra play a Brahms symphony in a concert hall, I listen attentively, but if I put a disk of that Brahms symphony on the stereo in my living room, I will reach for a book or magazine to read instead of closing my eyes and giving my full attention to the music? If I had the score to follow while the disk was playing, I would be pleased to do that, and it would also count as “doing something.” Anyway, that's my hangup.

If I were a better listener, I would be a better musician. It's obvious that I've taught myself to ignore music when it interferes with work I'm doing, a book I'm reading, or a tricky exit from a highway (the latter is a highly adaptive lapse of musical attention). Music isn't upward in my consciousness. I'm not talking about finding that my attention has wandered from the music while I'm at a concert. I'm talking about hearing music without listening to it, about relegating it to the background.

When I said that I would be a better musician if I were a better listener, I was thinking mainly about my efforts to play jazz and improvise, but it also goes for playing classical music or any music from written notes – alone, but more importantly when playing with other people. For many years I played alto saxophone in a community wind band. To play properly in a large ensemble like that, as many as thirty-five musicians in our case, you have to watch the conductor all the time, you have to read your notes, and you have to hear what the other musicians are doing so you'll stay in tune, stay in tempo, and match the dynamics and phrasing of the band. Usually that doesn't happen, which is why community wind bands can sound so dreadful – aside from the trite music they play. Recently I've been playing baritone saxophone in a big band, and that's even harder, because the rhythms are tricky and the playing is much more intense. If you don't listen to what the rhythm section is playing – the bass, the drums, the piano, and the guitar – you can't stay together with the band. And if each musician fails to listen to what the other saxophones, trombones, and trumpets are playing, the ensemble playing will be an ensemble in name only.

Listening is even more crucial and difficult when you're trying to improvise. You have to hear the song you're playing in you mind, including the harmonies, you have to hear what you're playing, and you have to hear what the rhythm section is playing. If you're playing with a good rhythm section, they will respond to you and vice versa. That means that everybody has to be listening to everybody else. You also have to listen to the other soloists when you're not playing, so that you'll know where to come in when they stop playing, or so that you can add a response to what they're playing, if that's the right thing to do. Or to be inspired by a great solo that might just be happening in front of you.

The only reason why it's possible to do this is the relative simplicity of most of the songs that jazz musicians improvise on. They tend to be thirty-two measures long, divided up into four eight-measure sections, three of which are essentially identical. The rhythm section (drum set, bass, guitar and/or piano) has the responsibility of maintaining that form, and if you're a good listener, you can tell where you are in the song by hearing the chords the rhythm section is playing. Though I've been improving steadily, I'm far from mastering the listening and playing skills you need to be a good improviser, and I usually find myself playing with rhythm sections on my own level – which means they get lost – so I have to know where they should be, even if they aren't actually there.

So how can I improve my listening? Here's my project. I'm going to pick a relatively short jazz piece that I really like – say a five-minute piece featuring by Sonny Rollins, one of my favorite musicians – and I'm going to listen to it systematically. First I'm going to play it and get a general impression. Then I'll focus on the drums, the bass, and the piano in turn. Finally, I'm going to listen to the horns – and I'm going to report on what I hear.

But wait a minute. What's this obsession with “doing something”? It's a superego trip, no question about that. The compulsion to feel that I'm doing something is a legacy from my Lithuanian Jewish forbears in combination with the American work-ethic that I imbibed while growing up. “Don't waste time” was the major imperative. There's a book out, which I haven't read, called Don't Just Do Something, Sit There, by a Jewish-Buddhist teacher with a sense of humor named Sylvia Boorstein. (She also wrote, That's Funny, You Don't Look Buddhist, which I did read.) I've attended several Buddhist silent meditation retreats, where “sitting there” is valued as “doing something,” and, in fact, it truly is doing something very powerful.

Like most people, I imagine, I waste a lot of time looking for keys and glasses, playing stupid games on the computer, waiting on lines, at traffic lights, and in other situations where precious time just seeps out onto the floor like coffee from a cracked cup. It makes me feel either guilty for spending my time pointlessly or angry because I am constrained to do something pointless. Then I try to use the wisdom I heard from a teacher at the first meditation retreat I attended. She said, “Suppose you do have to wait for twenty minutes on line at the post office. You're still with yourself.” She was right. Sometimes I deal with my own impatience by observing it and that of the other people on line. That's always instructive. Anyway, then I'm “doing something.” I'm observing human behavior, including my own.

The compulsion not to waste time is related with a pervasive feeling of dissatisfaction with myself, the constant obligation to improve myself (another legacy from Jewish Lithuania). So, I wonder about my project of listening carefully to a single jazz piece (at this very moment Sonny Rollins is playing “Just Friends” in the background) until I've really heard as much as I can of what all the musicians are doing separately and together on it. Is it just another obsessive self-improvement project, like remembering to put moisturizing lotion on my feet every morning, a sop to my superego? It certainly won't earn money for me, and that is definitely another criterion for “doing something”: if I'm paid for it, it counts.

At the 2006 international film festival in Jerusalem I saw a film called “The Pervert's Guide to the Cinema,” which was essentially a two hour interview with Slavoj Žižek, an energetic, engaging, and provocative philosopher, psychoanalyst, and cultural critic. In that interview, among a million other things, he spoke of the superego as a demonic presence in the psyche, which was something that I'd never grasped before. As Žižek pointed out, the superego can never be satisfied. It's always posing new demands (I always thought of the superego as a benign supervisor, telling me to do the right thing – which shows how much insight I have into myself!). So, thanks to Žižek, I recognize the voice in me, that's always telling me to “do something” as a demonic presence, not a rational call to organize my life better, to channel my emotions and instincts, to be good to myself (and others).

Perhaps I should be satisfied with the way I hear music now. I enjoy it.

But that's not true. The better I listen to music, the more I enjoy it. If I actually do this listening project and hear a piece a dozen or more times, taking note of what each of the musicians is doing, I'm sure it'll carry over to my less directed listening.

Choosing the Piece – Session One

I have been thinking about this project for months, and I have kept putting off the choice of the piece to work with – my analyst, if I had one, would tell me this was a sign of resistance, that this benign project is threatening to me in some way. The piece has to be short enough to be manageable – I'm not going to listen to a twenty-minute piece for as many times as it takes to hear it all – and it has to be great – if I'm going to devote time to this, the piece has to warrant it. But it also has to be fairly traditional, with a recognizable form and harmonic progression. Right now I'm leaning toward the pieces on a Sonny Rollins compilation called Airegin.

I finally settle on a tune called The Stopper, written by Rollins and originally released in an album called Sonny Rollins with the Modern Jazz Quartet, recorded by Prestige in 1951, when Sonny Rollins was just twenty-one years old and already an unbelievably brilliant, creative musician. On my first listening, I just try to get a general impression. I identify the instruments being played: tenor saxophone, vibraphone, piano, bass, and drums. I notice the tempo (rather fast but not blazing), and I see that the piece is based on the interplay between a quick melody, introduced by the saxophone, and a slower, syncopated, four note break played by the bass and the vibraphone (and maybe by the piano and drums, too – I have to check that out), which comes in frequently. I also notice that it is organized the way jazz performances for small ensembles are usually organized: the theme is introduced, the players improvise on the theme in turn, and then the theme is played again. The saxophone plays the theme and the first solo. Then the vibraphone plays a shorter solo, and finally the pianist solos before the theme is played for the last time. Finally, I cannot help noticing what is essentially the main point: Sonny Rollins' astounding virtuosity on his instrument, matched by both the vibraphone player (Milt Jackson) and the pianist (John Lewis).

The second time around, I decide to try to count out the length of the theme and, if I can, the length of the solos. Generally people talk about “choruses” in this context. A chorus is one full cycle in the piece, initially the melody from beginning to end, and then the improvisations, which are usually the same length as the melody or multiples of that length. I have to stop the playback after the first chorus, because I'm not sure whether there's an introduction before the song begins or whether they just leap right into the melody. In fact, after repeated listenings, I still am not sure I can hear where the first chorus begins and ends, and I am sorely tempted to look up the written music – but I resist that temptation. This exercise is about listening. (Anyway, later on, when I did succumb to the temptation, I couldn't find “The Stopper” in any of the numerous fakebooks I own).

Obviously the name of the piece, “The Stopper,” has something to do with the difficulty I'm having in hearing how it's structured: it stops and starts in surprising places. I'll give it one more listen before I call it a day.

At last I think I'm hearing it right: I'm quite sure it's a twelve-bar blues.

The vast majority of jazz songs are either twelve-bar blues or thirty-two bar standards. When I use the word “bar,” I'm referring to the graphic convention of dividing lines of written music with vertical lines, bar-lines. I must apologize for mentioning such elementary things, but often, when I try to write an explanation of something I know, I find I really don't know it all that well – I can't explain it clearly. So I'll try to explain this to myself. The other word we use for what the bar lines signifies is “measure.” Between every pair of bar lines in written music is a measure, which may contain any number of beats, from one to twelve or more. In most music I know of (with the exception of Gregorian chants) the written measure truly measures something – it makes sense to divide pieces up into measures, and the listener hears the division, even though melodies and phrases usually don't fit into them all that neatly. Gavottes, for example, a common baroque genre, always begin in the middle of the first measure.

So when I talk about a twelve-bar blues form or a thirty-two bar standard form, this generally refers to the number of (usually) four-beat measures there are in the whole tune. To figure out the form of “The Stopper,” I listened to it, counted out four beats, and marked the measures on my fingers. It didn't exactly sound like a blues to me when I was trying to parse it, so I tried to fit it into a thirty-two bar pattern first, and it wouldn't go. I would count as far as twenty-four measures, and then it started over again.

I began to feel frustrated. Why am I having so much trouble in the very first, the simplest stage? The listener encounters two problems in trying to hear the structure of any piece: (1) identifying the meter (two, three, four, or six beats per measure, usually) and (2) hearing what beat the piece starts on. In “The Stopper” the musicians play fast, and it's hard for me to decide whether to think of the basic beat as a quarter note (four beats to a measure) or a half note (two beats to a measure). I'm almost ashamed as I admit this – this sort of thing should be absolutely obvious on the first hearing, but it isn't always for me. That's why I'm doing this exercise with myself.

Session Two - Drummer

Although the form of the piece still eludes me – I'm not quite sure what's happening right at the beginning of it, and that throws me off until Sonny Rollins launches into his first solo – I decide to go on and do what I had planned to do, not get stuck. So I listen to the drummer, Kenny Clarke, of whom it says, on the web site called “Drummerworld”:

“[He] was a highly influential if subtle drummer who helped to define bebop drumming. He was the first to shift the time-keeping rhythm from the bass drum to the ride cymbal.” This means that instead of a steady thump-thump on every beat of the measure, or on the second and fourth beat, you hear a much more subtle, lighter “chang-changa-chang,” with a lot of hissing. It also means that the bass drum, operated by the drummer's foot, is now free to accentuate beats that the drummer wants to hit hard, giving him a lot more flexibility to vary the rhythm and make it more complex.

Why start with the drummer? Partly because I'm not in the habit of listening carefully to drummers, even though I know how important they are. I've played with reasonably good drummers and mediocre drummers, and I know that a good drummer can put your playing over the top, and a bad one can screw you up. The drummer does so much more than keep time, but if he doesn't do that, he can't do all the rest. He may not set the tempo, but he's got to keep it. He plays what are called “kicks,” accentuating places in the melody or filling in when the soloist is holding a long note. Mainly he gives energy and drive to the other musicians, pushing the music along. When the music is slow, he keeps it from falling asleep, and when it's a complex, active Latin polyrhythm, he's the busiest person in the ensemble. In fact drummers are always amazingly active, and I can't imagine how they keep going. Their job demands great physical stamina, speed, and incredible coordination along with fine musicianship. To appreciate the role of drumming in jazz, you don't have to get into the importance of the drum in African culture and the fact that plantation owners deprived their slaves of drums, to prevent them from communicating over long distances, but you do have to remember that rhythm is essential to African-American music, the father and mother of the now international and multi-racial genre known as jazz.

I listen to the piece twice, trying to hear what Clarke was doing, which isn't always easy, because he plays softly, and much of the time the other instruments drown out his sound – which doesn't mean that the other musicians aren't hearing him. He is definitely hearing them, and his drumming always supports what they do. There is a repeated pattern of accented notes in the piece. The drums reinforce the accents, and the rest of the time, when the musicians are playing fast passages, the ride cymbal whizzes along under them, not with separate beats so much as a shimmer of rhythm, like a wave they're riding, with occasional quick smacks on the snare drum. You hear him most strongly when he's most needed, under the piano solo that comes before Sonny Rollins plays the melody again at the end. He doesn't get to play a solo on this tune. After listening to Kenny Clarke here, I find myself paying much more attention to the drummers when I listen to other things during the day.

Session Three – Bass

The double bass plays a role in jazz quite different from the role it plays in a symphony orchestra, where it is typically bowed and reinforces the cellos. In jazz it's usually plucked, and it's one of the three pillars of what's known as the rhythm section – which, in fact, could also be called the harmony section. In early jazz recordings you won't hear a string bass for that very reason: the recording techniques weren't adequate to catch their sound. So you'll hear tubas. Today they're usually amplified, so you can really hear them, and sometimes musicians play bass guitars – but to my ear there's nothing like the acoustic sound of a bass viol.

Percy Heath, the bass player of the Modern Jazz Quartet, doesn't do anything that sounds very special in “The Stopper” – he just plays in fine synchronization with Kenny Clark's drumming, emphasizing the slow notes when “The Stopper” stops and then steaming along with rapid eighth notes, laying down the harmonic structure of the piece while keeping the rhythm going. This performance many not sound special, but Heath's technique is superb. He maintains the energy level and keeps the music together. The term usually used for what he does here is “walking,” but in “The Stopper” it's a lot more like trotting.

The exercise of listening to the music and concentrating on the two least conspicuous performers (in this case), the drummer and the bass player, who don't take solos here and whose playing is mainly supportive of the other musicians, creating the musical texture on which the melodies are embroidered is not easy. My attention is constantly seized by the more dominant musicians, who play melodies. But when I force myself to hear the bass, I hear what the melodists are building on.

Session Three – Piano

Technically, the piano is a percussion instrument: felt hammers hit the keys to make them sound. Thus the piano belongs in the rhythm section of a jazz ensemble. Of course the piano is also one of the most versatile musical instruments ever invented, and that versatility is fully expressed in work of outstanding jazz pianists, including John Lewis. In “The Stopper,” Lewis stays mainly in the background. He contributes to accenting the four note theme that keeps recurring in the piece, playing along with the vibraphone, bass, and drums, and in the passages of fast runs played by the two other soloists, he plays short, soft, syncopated chords – no arpeggios, runs, or ornamentation. Then, after the tenor sax and vibraphone have soloed, the piano plays a short solo, just one twelve-measure chorus – showing what it can do when it feels like it.

I have played in ensembles with a lot of amateur pianists, and they have an almost universal problem when it comes to playing by ear with other musicians: they play too much. When a pianist plays alone, she has to do everything, providing melody, harmony, rhythm, and ornamentation. When the pianist who's used to doing that faces the task of accompanying a soloist in an ensemble where there are already musicians playing the bass line and the rhythm, she doesn't know what to do, and she duplicates what's already being done, making the background heavy and crowded, not leaving the soloist room. But John Lewis, who could play any way he wanted, full or spare, loud or soft, with virtuosity or simplicity, doesn't play a single superfluous note here. His chords guide the listeners' ears – including the soloists' ears – only occasionally standing out with some big and dissonant sound, usually signaling what is known as the “turnaround,” the end of the twelve-bar structure, which, instead of resolving in a cadence, throws the melody back to the beginning.

Meanwhile, after listening to it a dozen times or more, concentrating on the background, I've finally figured out the form of the piece, the connection of the recurring theme made up of four slow notes and the intervening fast sections – it's definitely in the form of a blues, and the four note theme appears both at the beginning and the end of the twelve-measure form.

Because I have some experience as a musician and have taken classes in ear training, it isn't too hard for me to recognize the four note theme as a pattern very common in the movement of bass notes – in both jazz and classical music – one, six, two, five. By playing another instrument along with the record, I quickly figure out that these notes are Bb, G, C, and F. In the first two measures, each note is given two beats: Bb, G; C,F. Then in the next two measures, each note gets one beat, and the pattern is repeated: Bb, G, C,F; Bb, G, C, F. Importantly, those four notes, which themselves are quite ordinary and repeated any number of times, are mainly not played directly on the beat, so instead of creating a static, boring, predictable pattern, they give energy and drive to the piece. As I said, in other jazz standards, those notes are usually given to low instruments to play, and the listener mainly hears the chords and melodies built on top of them – but in “The Stopper” they are so prominent that it's hard to decide whether they, in fact, are the tune, and what Sonny Rollins plays is ornamentation.

Session Four – Vibraphone (and Saxophone)

In the long career of the Modern Jazz Quartet, the vibraphone, played by Milt Jackson, was the main melodic instrument. Here Jackson defers to the guest artist, the young Sonny Rollins – of course back in 1951, Milt Jackson was also no old man. Here he starts off by playing the one-six-two-four theme with the rhythm section. The twelve bar blues is divided into three four bar sections, as one would expect. In the first two of these, the long notes alternate with swift runs by the saxophone, and in the ninth and tenth measures the saxophone takes off, playing short, fast phrases, which are echoed by the vibraphone. In the eleventh measure, the four note theme reappears, and in the twelfth and final measure of the melody, the saxophone plays a phrase that leads back to the beginning of the piece, since the melody is repeated. After they play the melody through again, Sonny Rollins launches into three choruses of improvisation, during the first of which the rhythm section, including the vibraphone, play the four note theme again as a background to the solo.

Rollins is playing the tenor saxophone about as fast as it is humanly possible to play, and in one or two places, it sounds to me as if his fabulous technique comes close to failing him. Not only is he playing great music, he's also challenging the soloist to follow him: can you keep up with me? After Rollins, Jackson plays a two chorus solo, showing that he can keep up with ease, and then some. He uses some of the melodic ideas that appeared in the saxophone solo, with consummate finesse, and then he and Rollins lay out for the chorus while the piano solos, before the quintet plays the melody again, like the first time, and conclude the piece.

The solos are mainly in fast eighth notes, and they go by too quickly for my ear to catch the individual notes – I mainly hear contours, which is probably what most people hear, rising, falling, and twisting melodic lines. To hear the individual notes of the solos, I use Audacity, a free sound-editing program that I have downloaded. The program enables you to listen to the music at the same pitch, but twice as slowly (or even slower). Though it makes the sound of the saxophone ragged and raspy, it lets you hear what Sonny Rollins is doing during his solos, as well as everything that's going on behind him, and it makes me wonder how they could all think so fast musically. If I listen to his solo often enough, played at half speed, there's some possibility that I might learn to play it (slowly) and be able to write down the notes. I've never done the highly recommended exercise of transcribing solos – maybe this is the time.

The Moral

By now I'm hearing more detail in “The Stopper” every time I play it for myself. It took considerable patience to get there, but I surprised myself. At first I was frustrated. I heard much less than I thought I should be hearing, and I kept wishing I had the written notes – because I'm used to that. But I've clearly hit on a method of listening that works for me, one that I can recommend. It's certainly time intensive. “The Stopper” lasts just three seconds shy of three minutes, and I've probably spent more than two hours listening to it. The issue is: How does one spend so much time listening to one piece without getting bored with it? At a jazz school I attended, I had the good fortune of encountering Chris Batchelor, a British trumpet player, who talked about the huge amount of “information” you can get out of just listening, for example, to what the bass drum is doing in a given piece, if the drummer is good. The more such information you hear when you listen to music, the more exciting the music gets.

Jazz solos like those by Sonny Rollins, Milt Jackson, and John Lewis in “The Stopper” give us a chance to hear spontaneous musical creativity. Playing like that is a risky activity, because a lot can go wrong, and you never know exactly what's going to happen. Listening to music like this when it's been recorded, and you can hear it as many times as you want to, is very different from listening to it live, when it's gone as soon as it's over. In this case the musicians were playing in a recording session, knowing that they could discard performances they didn't like, and some of the spontaneity of live jazz improvisation was lost – they must have planned the order and number of solos and decided exactly how they would begin and end it. I doubt very much, however, that the music was ever written down. All the musicians knew the standard chord progression of the blues, and the phrases that Rollins plays would be easy for a man with a phenomenal musical memory like his to play by ear.

As for the piece being a blues, as I said, I doubt that many listeners, hearing it for the first time, would hear it as a blues. It certainly doesn't have the haunting kind of melody we associate with a blues. In that sense, it's like several Charlie Parker tunes (such as “Billie's Bounce,” “Chi Chi,” or “Au Pivave”), which could be interpreted as self-conscious, modernist commentary on the blues form – using it to do something new and different, difficult and sophisticated. Rollins' playing especially, with the shimmering cymbal underneath it, driving it forward, sounds aggressively brilliant: listen to me! He's a young man with great, infectious energy, already at the top of his ability, commanding attention with bravura. He may be playing a blues, but he definitely doesn't have them!