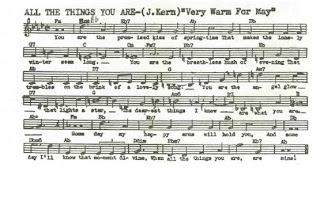

in Praise of a Song

This song has been played so many times that people take the elegance of its construction for granted. When you learn to play the melody, you appreciate the logic of it, the way it descends from the first A flat down to a B natural in the fifteenth measure, leaps up to a D natural, again descends to a G sharp, which metamorphoses into an A flat and begins a descent again, a descent which is interrupted with some upward leaps, until it finally settles on an A flat, the basic tonality of the song, at the end. It's deceptively simple, deceptive because the descents move through some surprising notes that don't belong to the key in which the song is written.

Harmonically, it is very sophisticated. It starts off by establishing the key of A flat major in the first four measures, with an absolutely ordinary sequence of chords, VI7-II7-V7-I, which one typically finds at the end of a classical piece. In the next four measures, it takes us to a surprising place harmonically with a daring transposition that sheds four flats in three measures, by moving from D flat major (a chord appearing in the key of A flat with no accidentals) to G7 (a chord that sheds two of the flats of A flat, the B flat and the D flat), which resolves to C major.

Then it jumps back to a key much closer to the original key of A flat major, when the C major chord turns into a C minor chord, and we have a repetition of the initial chord series (VI7-II7-V7-I) but in the key of E flat, the dominant of A flat – so after the digression to the unrelated key of C major, we have returned to a harmonic movement typical of classical movement: modulation to the dominant. However, instead of staying in that key, in a sequence of chords identical to that of measures five to eight, but transposed up a fifth, we modulate to the entirely unrelated key of G major, exactly one half tone below the initial key of A flat major, which means that in the space of sixteen measures, the song has moved almost as far as possible from the originally key. (If you lay out the twelve possible keys in the diatonic scale in the order of the cycle of fifths, you get:

Ab – Db – Gb (F#) - B – E – A – D – G – C – F – Bb – Eb- Ab

So the keys of either A or D would actually be farther away from A flat than the key of G, but it's still a very bold modulation.)

The third eight measures of the piece, the bridge, begins by establishing the key of G major with chord progression typical of classical harmony: II – V7 – I. Then, however, the second half of the bridge jumps to an unexpected key: E major. The chord progression that Jerome Kern (assuming that the chords that appear above are the ones he wrote) put in is A minor, B seven, E major. The A minor seems to be repeating the chord progression of the first four measures of the bridge, but instead of being II in the key of G major, it becomes IV in the key of E major, since the following chord is a B seven. In fake books that reflect the way jazz musicians have reharmonized the song, an F sharp half diminished chord is substituted for the A minor (the chords have almost the same notes, F#, A, C, E and A, C, E, G respectively), so you have what jazz musicians call a two-five to E – except ordinarily the half diminished chord ordinarily indicates a minor key, and this progression leads to a E major. The last chord of the bridge, on the twenty-fourth measure, is A flat augmented (Ab, C, E) – a chord that can be also be thought of as C augmented and E augmented, because it's made of three equal intervals, major thirds. Harmonically, augmented chords don't fit into any ordinary diatonic scale (except the melodic and harmonic minor scales, which are not, strictly speaking, ordinary), and composers use them to shift keys almost any way they want to. Here, if you think of the chord as a C augmented chord, it can be used to move the harmony back to F minor, which is where the piece began.

The last part of the song repeats some of the material from the first part but expands on it, and, unlike the first part, it finally lands squarely in its home tonality: A flat major. The chords in the first five measures of this section are the same as those of the first five measures of the piece, but instead of jumping to an unexpected G7 chord after the Db7, the way Kern wrote it, it stays in the tonal territory of Db, the sub-dominant of Ab major and ends with a classical cadence: Bb min7 - Eb7 – Ab. Those measures are reharmonized in various ways in different fake books that I have seen, to make the final cadence stronger.

Another way of thinking about the harmonies here would be to say that the song can't decide, at first, whether it's in Ab or C. The first eight bars end on C, the second eight bars end on the dominant of C, G, and the bridge starts off in G. The bridge ends in the key of E major, which is exactly halfway between C and Ab, and the final chord of the bridge is that augmented chord which fits both into the key of C (C,E) and of Ab (Ab,C). In the last twelve bars (in the printed version I appended at the beginning, the final bar of the piece is missing), the song makes up its mind. If the last part of the song were a simple reprise of the first eight bars, which is very common in the type of song known as “standards,” to which “All the Things You Are” definitely belongs, it would in fact end in the key of C. However, the second to last four bars, which correspond to bars five through eight, and on a d diminished chord, as Kern as harmonized it. (In some fake books this appears as a B diminished chord, which is made up of exactly the same notes, with a different bass.) From there Kern puts us squarely in the key of Ab major, although the second to last melody notes, F, G, could actually be heard as the seventh and root of G7, resolving into C major rather than Ab!

1 comment:

Thank you! This really helped me understand the changes. -Ed

Post a Comment